Ownership in Rust

Understanding ownnership

Ownernship model is a way to manage memory in Rust. To understand why we need this model, we need to first understand the typical way programming languages manages memory:

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| Garbage collection |

|

|

| Manural memory management |

|

|

| Ownership model |

|

|

Warning

Although Rust is Error Free in Memory management, you can opt out and do memory unsafe operations using unsafe block, at which you should know what you are doing.

Stack and Heap

During runtime our Rust program has access to both Stack and Heap.

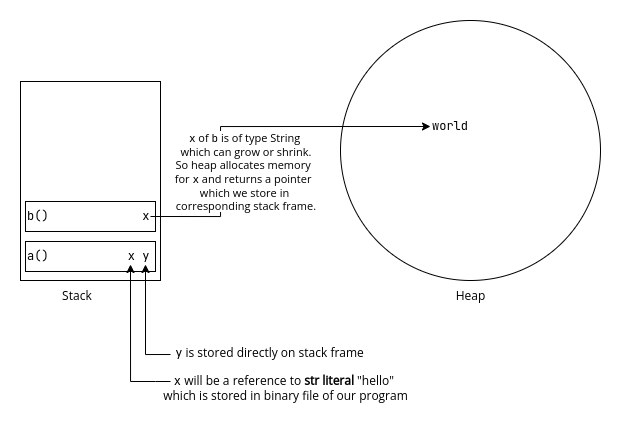

- Stack: fixed size and cannot grow. Stack stores stack frames which are created for every function that executes, which stores the local variables of function being executed. The size of stack frame is calculated at compile time.Variables live only as long as the stack frame lives.

- Heap: Less organized, grows and shrink at run time, the data stored in the heap could be dynamic. We control the lifetime of the data

fn main() {

fn a() {

let x: &str = "hello";

let y: i32 = 32;

b();

}

fn b() {

let x = String::from("world");

}

}

When a() get executed it's stack frame is created, which calls b() which creates it's own stack frame. When b() finished it's execution, it's get popped off, all of the variables get's dropped. Then finally a() finishes and it's variables are dropped.

Success

-

Pushing to Stack is faster than allocating it to heap, because the heap has to spend time looking for place to store new data.

-

Accessing data on stack is faster than accessing data on because with heap you would have to follow the pointer.

Ownership Rules

Ownership Rules

- Each value in Rust has a variable that's called its owner.

- There can only be one owner at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Variable Scope

fn main() {

{ // s is not valid, because it's not yet declared

let s: &str = "hello"; // s is valid from this point forward

} // scope ends, and s is no longer valid

}

s is str literal, as stated, it will be stored inside binary with reference in the stack.

But if, we were to use String which is dynamically sized,

fn main() {

{ // s is not valid, because it's not yet declared

let s: String = String::from("hello"); // s is valid from this point forward | allocate

} // scope ends, and s is no longer valid | deallocate

}

new keyword and then deallocate after you're done with it with delete keyword.

In Rust, this happens automatically. It autmatically allocates memory on Heap, and when scope ends it deallocates.

Memory and Allocation

A simple type stored on Stack, such as integer, booleans, characters implement Copy trait, allowing them to be copied instead of being moved.

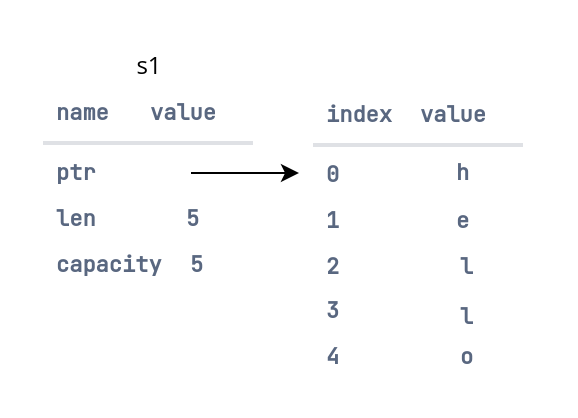

The String is made up of three parts:

1. A pointer pointing to the actual memory allocation on heap.

2. length of string.

3. Capacity, actual amount of memory allocated for String.

s1 to s2, the String data is copied, i.e., the pointer, the length, and the capacity that are on stack. The data on the heap that both the pointers of s1 and s2 remains as it is.

To ensure memory safety, after this line, Rust invalidates s1.

This might sound like making a shallow copy, the concept of copying the pointer, without copying the data. But since Rust invalidates the first variable it's called a move.

And so when running this program

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1; // Move, not a shallow copy

println!("{}, world!", s1);

}

error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `s1`

--> src/main.rs:5:28

|

2 | let s1 = String::from("hello");

| -- move occurs because `s1` has type `String`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

3 | let s2 = s1;

| -- value moved here

4 |

5 | println!("{}, world!", s1);

| ^^ value borrowed here after move

|

= note: this error originates in the macro `$crate::format_args_nl` which comes from the expansion of the macro `println` (in Nightly builds, run with -Z macro-backtrace for more info)

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0382`.

warning: `playground` (bin "playground") generated 1 warning

error: could not compile `playground` due to previous error; 1 warning emitted

To clone the string, call clone method on s1, which is bit expensive.

Ownership and Functions

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello");

takes_ownership(s);

println!("{}", s);

}

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) {

println!("{}", some_string);

}

Running this the compiler complains:

error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `s`

--> src/main.rs:4:20

|

2 | let s = String::from("hello");

| - move occurs because `s` has type `String`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

3 | takes_ownership(s);

| - value moved here

4 | println!("{}", s);

| ^ value borrowed here after move

|

= note: this error originates in the macro `$crate::format_args_nl` which comes from the expansion of the macro `println` (in Nightly builds, run with -Z macro-backtrace for more info)

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0382`.

error: could not compile `playground` due to previous error

s cannot be borrowed after it has been moved, which happens when pass in s to takes_ownership(). This is memory safe since some_string gets dropped after the scope of takes_ownership() ends.

Let's look at another example

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello");

takes_ownership(s);

println!("{}", s); // gives error, s is moved

let x = 5;

makes_copy(x);

println!("{}", x); // works because primites get's copied to makes_copy

}

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) {

println!("{}", some_string);

}

fn makes_copy(some_integer: i32) {

println!("{}", some_integer);

}

Returning string moves ownership to s1

fn main() {

let s1 = gives_ownership();

println!("s1 = {}", s1);

}

fn gives_ownership() -> String {

let some string = String::from("hello");

some_string

}

Take ownership and give it back

fn main() {

let s1 = gives_ownership();

let s2 = String::from("hello");

let s3 = takes_and_gives_back(s2);

}

fn gives_ownership() -> String {

let some string = String::from("hello");

some_string

}

fn takes_and_gives_back(a_string: String) -> String {

a_string

}

References & Borrowing

Rules of references

- At any given time, we can have either one mutable reference or any number of immutable references.

- References must always be valid.

What if we wanted to use a variable without taking ownership? We can use references, which do not take ownernship of the underlying values.

Maybe in situation like this, where we are just calculating the length of string:

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(s1); // s1 gets moved to function

// trying to borrow a moved value, s1

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: String) -> usize {

let length = s.len(); // len() returns the length of a String

length

}

Let's make the parameters of calculate_length() to take a reference of s and pass a reference when calling this function.

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&s1); // s1 gets moved to function

// trying to borrow a moved value, s1

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

let length = s.len(); // len() returns the length of a String

length

}

Info

Passing in references as function parameters is called borrowing because we're borrowing the value but we're not actually taking ownership.

- References are immutable by default.

If we wanted to modify the value, without taking ownership, we would do something like this:

Consider change() wants to modify s1 using an immutable referece:

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

change(&s1);

}

fn change(some_string: &String) {

some_string.push_str(", world");

}

s1 mutable, because mutable references will work only when there is mutable variable underneath.

2. Pass a mutable reference.

3. Accept a mutable reference in change().

fn main() {

let mut s1 = String::from("hello");

change(&mut s1);

}

fn change(some_string: &mut String) {

some_string.push_str(", world");

}

Mutable references have one restriction

You can only have one mutable reference to a particular piece of data in a particular scope.

This prevents data races at compile time.

You cannot do, something like this:

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &mut s;

// cannot borrow `s` as mutable more than once at a time

let r2 = &mut s;

println!("{}, {}", r1, r2);

}

To fix these, make these references immutable.

But can we mix mutable references with immutable one?

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s; // these references are still immutable

let r2 = &s;

// cannot borrow `s` as mutable because it is also borrows as immutable

let r3 = &mut s;

println!("{}, {}", r1, r2);

}

Warning

You can't have a mutable reference if an immutable reference already exists.

Note

Note that the scope of a reference starts when it's first introduced and ends when it's used for the last time. And so we can introduce a mutable reference after the println!:

Dangling References

A reference that points to invalid data.

fn main() {

let ref_to_string: &String = dangle();

}

// this returns a reference to string

// but when this function finishes executing, Rust drops `s`.

// The reference is invalid since the variable will not exist

// Rust prevents this from happening

fn dangle() -> &String {

let s = String::from("hello");

&s

}

The compiler complains:

error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier

--> src/main.rs:9:16

|

9 | fn dangle() -> &String {

| ^ expected named lifetime parameter

|

= help: this function's return type contains a borrowed value, but there is no value for it to be borrowed from

help: consider using the `'static` lifetime

|

9 | fn dangle() -> &'static String {

| +++++++

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0106`.

error: could not compile `playground` due to previous error

The Slice Type

Slices lets us reference a contiguous sequence of elements within a collection instead of referencing the the entire collection. Slices do not take ownership.

Why slices are useful? Let's imagine a problem where we'd want to return the first word, we don't have a way to return part of the string, but we can return an index to end the first word.

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("Hello world");

let word = first_word(&s);

s.clear(); // this makes `s` an empty string, `word` still remains 5.

}

fn first_word(s: &String) -> usize {

let bytes: &[u8] = s.as_bytes();

// iter() let's us iterate `bytes` without taking ownership

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return i;

}

}

s.len()

}

There are few problems with this code: 1. The return value is not tied to the string, requires manual synchronization.

word remains 5, even though s is empty at line 4.

2. When we want to change the implementation. If we wanted to determine the second word, we'll return starting and ending index, which needs to be synced.

To solve these issues, introduce string slices:

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("Hello world");

let hello = &s[0..5]; // creates a slice of s from 0 to 4 (5 is exclusive)

let world = &s[6..11];

let word = first_word(&s);

s.clear(); // error! mutable borrow occurs here

// But this won't work, as s.clear() mutates string,

//and we're passing immutable reference to `first_word()`

println!("The first word is: {}", word);

}

fn first_word(s: &String) -> &str { // return a string slice

let bytes: &[u8] = s.as_bytes();

// iter() let's us iterate `bytes` without taking ownership

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return &s[0..i];

}

}

&s[..]

}

To fix this modify it as follows:

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello world");

let s2: &str = "hello world"; // string literals are acutally slices

// this still works; `&String` gets coereced to `&str`

// let word = first_word(&s);

let word = first_word(s2);

}

// we want this function to also work with string slice

fn first_word(s: &str) -> &str { // return a string slice

let bytes: &[u8] = s.as_bytes();

// iter() let's us iterate `bytes` without taking ownership

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return &s[0..i];

}

}

&s[..]

}

Note

We can simplify string slices:

Slices on different types of collections